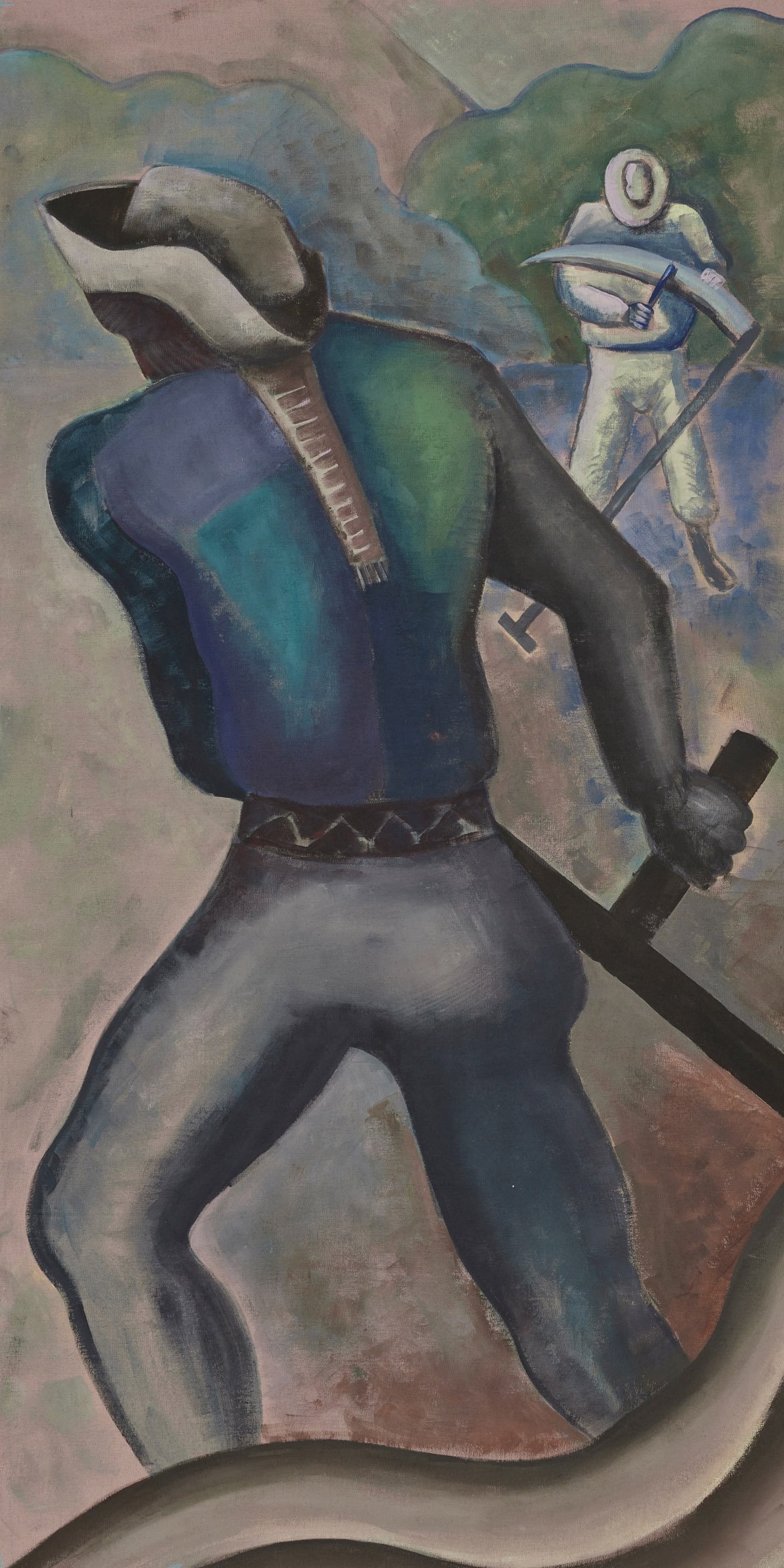

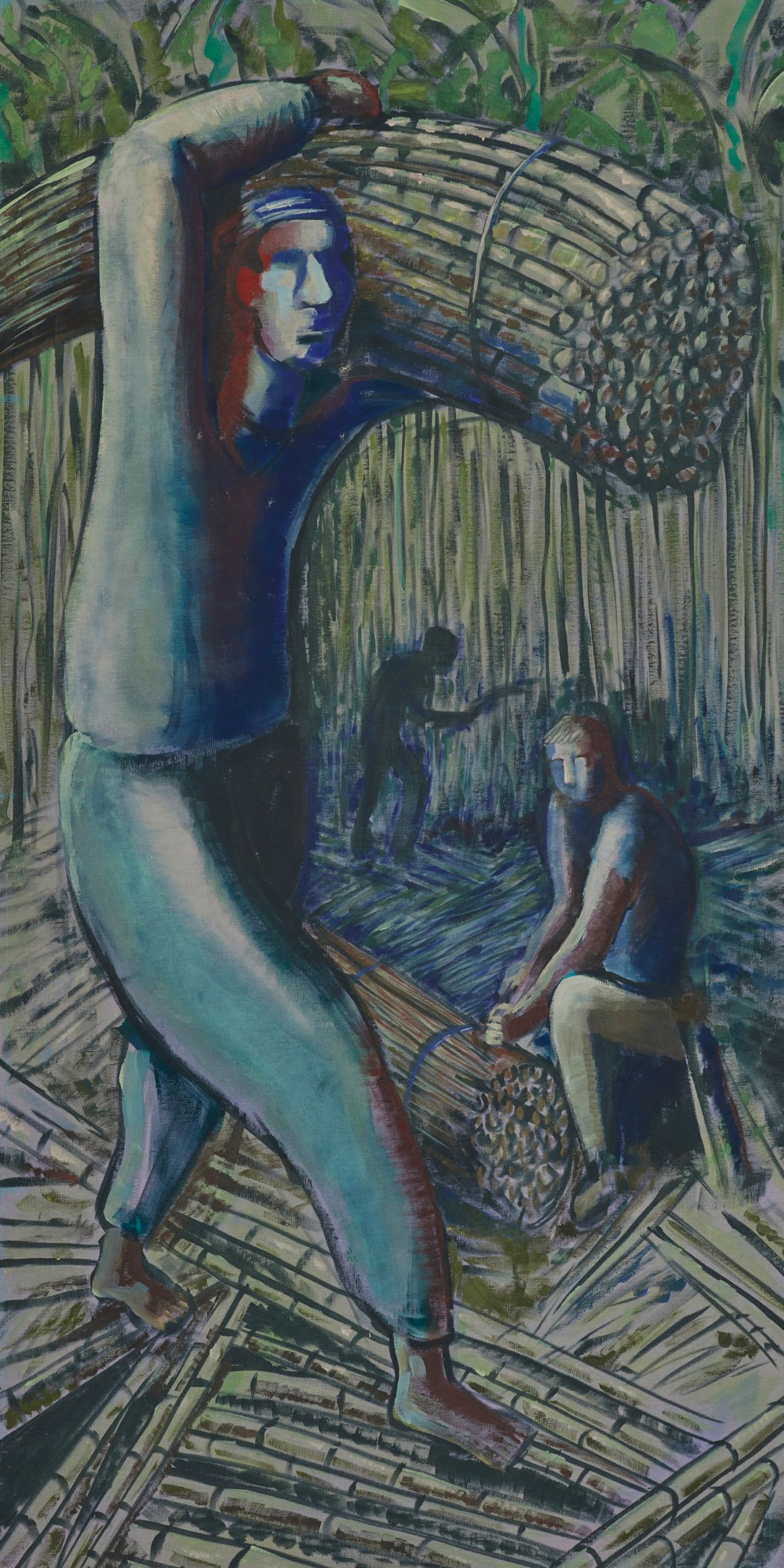

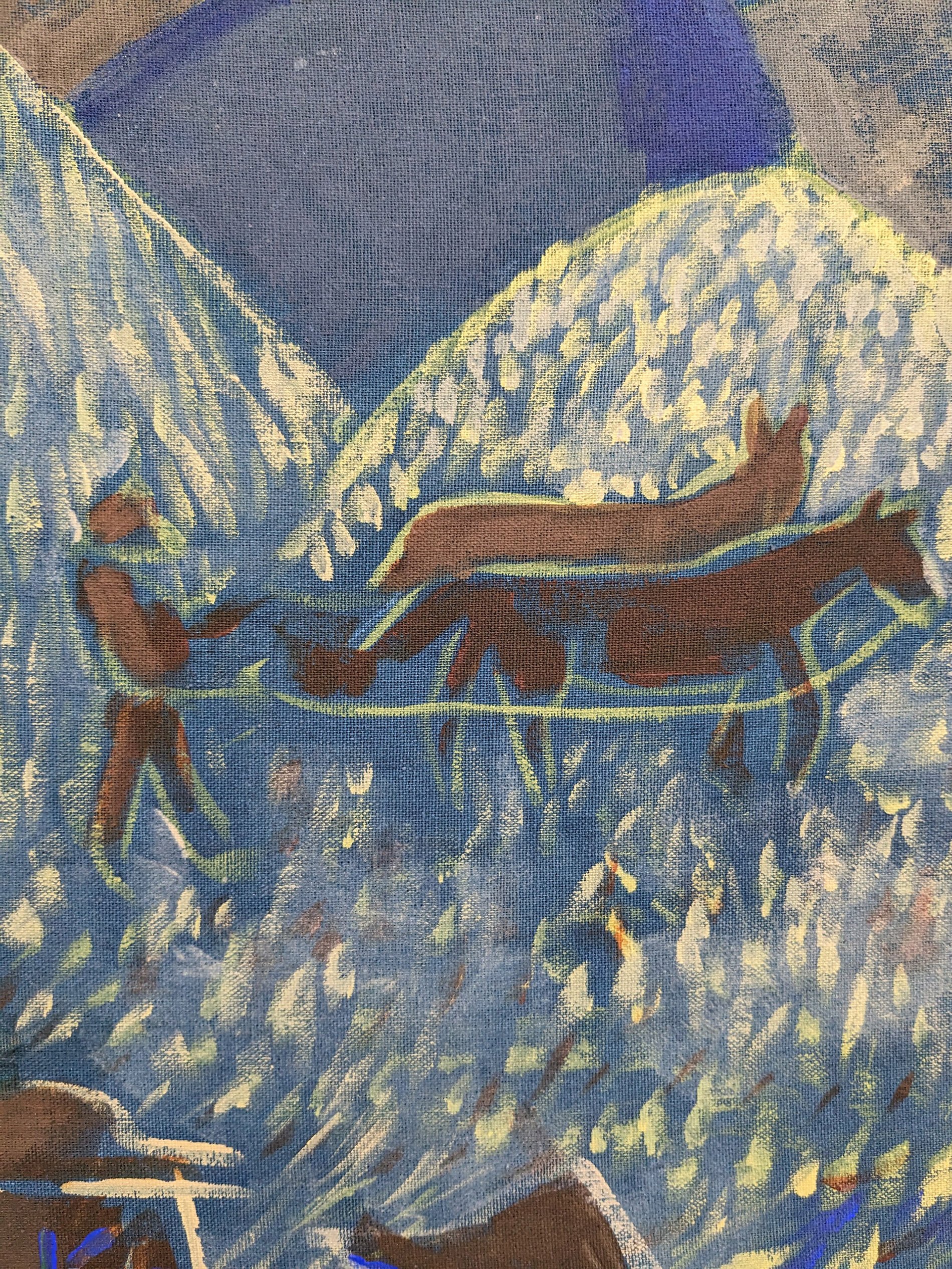

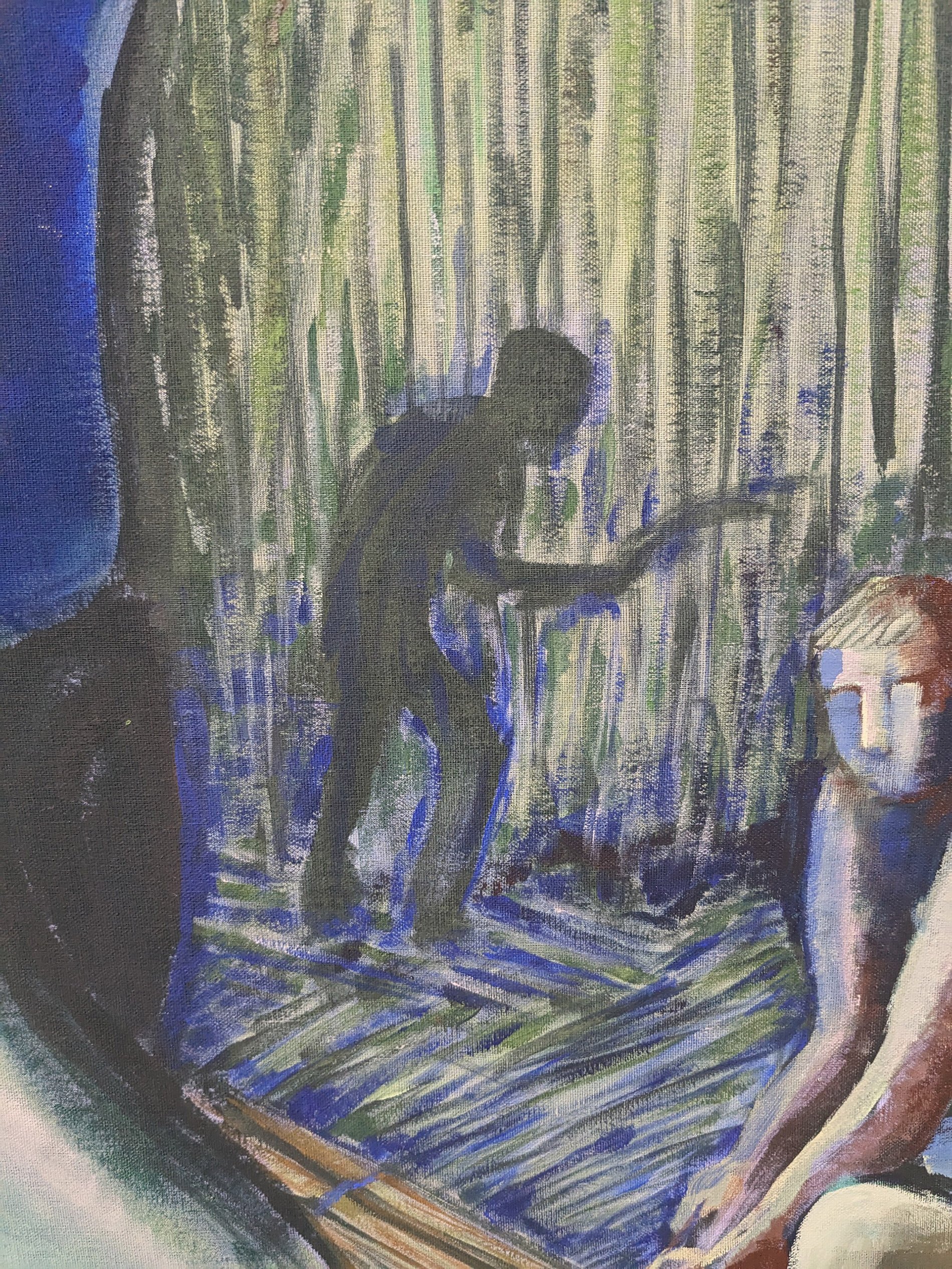

A stroll, though not the kind that is satisfied with a postcard view. It is a look at a specific time in the countryside that, between the 1920's and 1950's, was filled with figures that fractured the image that pervaded the Andean region since the inception of the republics, where the peasantry was considered backward and degraded. The indigenist gaze changed the perception of work tools as markers of technical backwardness, and encouraged people to think of a modernity anchored in native traditions. At times, they even became weapons to stand up against the hacienda regime. Peasant bodies also found new strength, leaving behind the social construct that swayed between melancholy over the lost past and their racialized portrayal as beasts of burden.

In recent decades, after the defeat of social movements in the second half of the 20th century —except for Bolivia and Ecuador— these imaginaries have returned, and define the peasantry as a subject only concerned with its own survival and incapable of participating in a revolutionary project. The works Iosu has used as a point of departure for this stroll through last century's figurative art correspond to a time when the Indian problem and land conflicts, according to the words of Mariátegui in 1928, were seen for the first time as an economic and political issue. This constituted a change from prior readings that claimed their souls needed to be saved, schooled or subjected to de-indigenization through mestizaje. The novelty of the revolutionary indigenismo in the 1920s in the Andean region consisted in understanding that indigenous freedom relies in attacking forms of land ownership and peasant work exploitation, and reorganizing work in communal forms, deeply rooted in the history of these lands. Political vanguard encouraged the shaping of indigenism as an artistic avant-garde, and the latter transmitted visually, at least for a while, the radical premises of the former.

Iosu tends to periodize, to segment a portion of time to examine something in the past and turn our attention to issues that have lost historical substance in the present. Behind these works lies the certainty that the Latin American countryside was for a long time the place for revolution, for the emergence of a new subjectivity that had to be depicted and contoured with precision. The bodies, the labor, and the landscape as a pictorial genre underwent a profound transformation whose force is today diluted in art history. The indigenist avant-garde fractured time in the region: the indigenous present was now loaded with a history denied by colonizers, landowners, and the bourgeoisie. From that point, a different future could be reinvented, sometimes nationalist, at others, socialist. As a result, a new way of viewing and imagining the rural world was born, which persisted until the end of the 1970s. This perspective also had limitations, of course, as a consequence of the disconnection between artistic indigenism and the social movements that supported it.

However, the outbreak of rebellions in recent years invites us to revisit past revolutionary figures in Latin America, because there is something in them that returns to the present and demands to be reconsidered as part of the visual repertoire of current social struggles. Iosu invites us to reconsider these ways of figuring the countryside and to bring them to the present to attend our pending appointment with the past, as well as to look beyond, in the clouds, above the newly opened horizon.

Mijail Mitrovic

Un paseo, pero no de esos que se contentan con la vista de postal. Se trata de mirar un campo preciso que, entre los años 20 y 50 del siglo pasado, se llenó de figuras que quebraron la imagen que permeó el área andina desde el inicio de las repúblicas donde el campesinado aparecía como un sujeto atrasado y degradado. Con la mirada indigenista, las herramientas de trabajo dejaron de verse como índices del atraso técnico y se volvieron invitaciones a pensar una modernidad anclada en las tradiciones autóctonas. A veces, inclusive, se alzaron como armas contra el régimen de hacienda. Los cuerpos campesinos también adquirieron una nueva fuerza, dejando atrás el imaginario que oscilaba entre la melancolía por el pasado perdido o su presentación racializada como bestias de carga.

En décadas recientes, tras las derrotas de los movimientos populares de la segunda mitad del siglo XX —a excepción de Bolivia y Ecuador—, estos imaginarios han regresado y ubican al campesinado como un sujeto solamente preocupado por su supervivencia e incapaz de inscribirse en un proyecto revolucionario. Las obras que Iosu ha tomado como base para este paseo por la figuración del siglo pasado responden a los tiempos donde el problema del indio y de la tierra, siguiendo la formulación de Mariátegui de 1928, eran vistos por primera vez como un asunto económico y político, ya no desde las miradas que planteaban que hacía falta redimir sus almas, llevarlos a la escuela o desindigenizarlos a través del mestizaje. La novedad del indigenismo revolucionario de los años 20 en el área andina consistió, precisamente, en comprender que la liberación del indio radicaba en atacar las formas de propiedad de la tierra y de explotación del trabajo campesino, y recuperar las formas asociativas de organización del trabajo que se hunden en la historia de estas tierras. La vanguardia política alentó la configuración del indigenismo como vanguardia artística, y ésta última tradujo visualmente, al menos por un tiempo, las premisas radicales de la primera.

Es usual que Iosu periodice, que recorte tiempos para examinar algo del pasado y devolver nuestra atención a asuntos que han perdido sustancia histórica en el presente. Detrás de estas obras late la certeza de que el campo latinoamericano fue por mucho tiempo el lugar de la revolución, del surgimiento de una subjetividad nueva que era preciso figurar y darle contornos precisos. Los cuerpos, las labores y el paisaje como género pictórico entraron en una transformación profunda cuya fuerza hoy se encuentra diluida en la historia del arte. La vanguardia indigenista quebró el tiempo en la región: el presente indígena estaba ahora cargado de una historia negada por colonizadores, terratenientes y burgueses, y desde allí podría reinventarse un futuro distinto, a veces nacionalista, a veces socialista. De todo ello surgió un nuevo modo de mirar e imaginar el mundo rural que se mantuvo activo hasta fines de los años 70. Esa mirada también tuvo limitaciones, desde luego, fruto de la desvinculación del indigenismo artístico y los movimientos sociales que le dieron sustento.

Los estallidos de rebeliones de los últimos años, sin embargo, invitan a mirar nuevamente el pasado de las figuraciones revolucionarias en América Latina, porque hay algo en ellas que retorna al presente y reclama ser reconsiderado como parte del repertorio visual de las actuales luchas populares. Ese es el paseo al que Iosu invita: mirar otra vez estas formas de figurar el campo y traerlas al presente para atender a nuestra cita pendiente con el pasado. Y también mirar más allá, en las nubes, arriba del horizonte nuevamente abierto.

Mijail Mitrovic